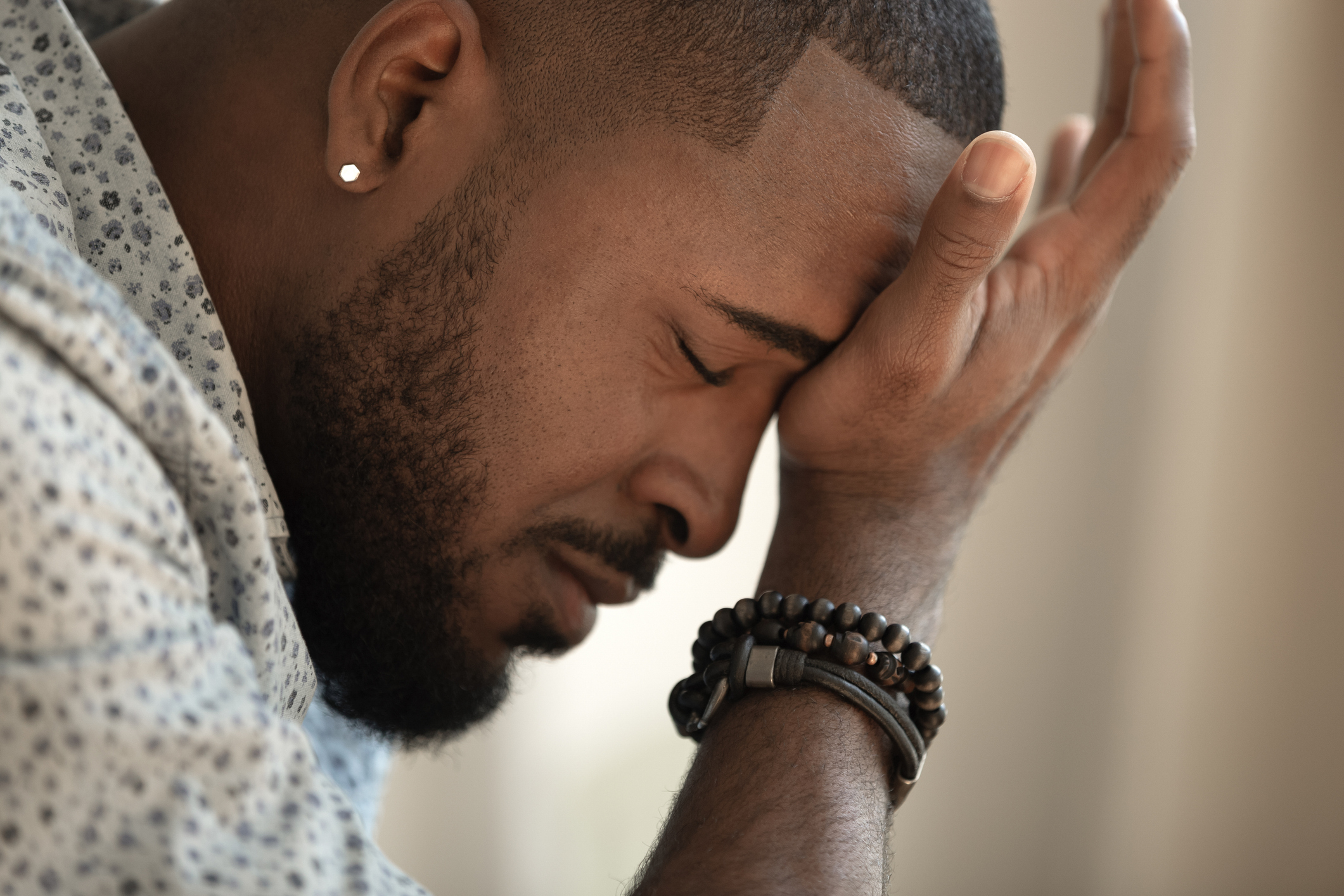

How Chronic Pain Can Impact Your Mental Health When You Have Kidney Disease

By Hannah Calkins

Chronic pain and depression are closely linked and because as many as 60 percent of hemodialysis patients report moderate to severe chronic pain, it’s likely that many of them have experienced depression—or are at risk for it. But it may not look or feel the way you expect, according to psychologist Robert Kerns, PhD.

“Depression among people with chronic pain may not be experienced as profound sadness,” says Kerns, a professor of psychiatry, neurology and psychology at Yale University. “Other symptoms may be more likely to be present, including loss of interest or engagement in activities you normally enjoy, as well as sleep and appetite dysfunction.”

Together, chronic pain and depression can impact management of your kidney disease and take a toll on your quality of life. Fortunately, effective treatments are available, and with the help of medical and mental health professionals, there are steps you can take to feel better.

How Chronic Pain Can Lead to Depression

First, it may be helpful to understand how chronic pain and depression are connected. Psychologist Ravi Prasad, PhD, says the same areas of the brain are involved in regulating both pain and emotion, which is one reason why the two conditions can overlap. But there are other factors at play, he says.

When people living with chronic pain are unable to do the things they want to do, they may pull away from activities that give their lives meaning. Their sleep may be affected. Their motivation may diminish, says Prasad, who is a clinical professor and director of behavioral health in the division of pain medicine at the University of California Davis School of Medicine.

As the pain condition evolves, the depression does too, he says, leading to a “vicious cycle.”

It makes sense, then, that people with depression are less likely to be successfully engaged in pain care, which can lead to less effective treatment for their depression, says Kerns.

At the same time, other biological, psychological and social factors may increase your likelihood of developing depression if you have chronic pain, says Kerns. These factors include a family history or genetic predisposition to depression, prior experience of trauma, or economic stressors.

“Some people may also engage in what is known as ‘catastrophizing,’ or pervasive negative thinking that may magnify the experience of pain and increase the likelihood of depression,” says Kerns.

Examples of such thoughts are “my pain is horrible”; “it will never get better”; and “I’m helpless,” he says.

Treatments That Work

Chronic pain and depression are complicated to treat. However, evidence-based approaches can alleviate the suffering caused by both conditions—as long as both conditions are addressed.

A major challenge is that people with chronic pain often believe that if their pain were treated effectively, their experiences of depression would also go away, says Kerns. “Evidence suggests this is not the case.”

Prasad agrees. That’s why both chronic pain and depression need to be treated concurrently, he says. Your doctor and a mental health professional can help determine which treatment will work best for you.

Treatment for depression may consist of medication, psychotherapy or both. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may be especially helpful, says Prasad.

“CBT helps people become more aware of the thought processes that influence their emotional and behavioral health outcomes,” says Prasad. “You can apply these strategies to coping with pain and with depression.”

If you’re able to engage in some physical activity, that may help too, says Prasad. “Exercise won’t fix the problem, but it can help you manage your symptoms,” he says. “If you’re active, you may get better rest, which gives you more energy, and that may motivate you to participate more in the activities you care about. Which, in turn, can improve your mood.”

How to Get Help

Your physician or nephrologist may not recognize the signs of depression, so it’s important that you speak up if you think you might need help. Let your doctor know if you are feeling sad, anxious, hopeless or guilty; are persistently restless, listless or irritable; are experiencing disturbances in your sleep or appetite; or have lost pleasure in activities you normally enjoy.

If you can’t access treatment, or if you’re interested in learning more about managing pain and depression on your own, Kerns says there are other resources available. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) requires annual depression screenings for patients on dialysis. Your dialysis social worker is trained to provide supportive counseling and can help you cope with your feelings.

“There are great books available to support people with both of these conditions, as well as a growing number of evidence-based self-management programs available on the web or for use on smartphones,” he says.

If you have chronic pain and are concerned about depression, you aren’t alone, and help is available. But at the same time, Kerns says, people with chronic pain should understand that depression is not an inevitable consequence of pain.

“Even though rates of depressive disorder are high among people with chronic pain, most people with chronic pain—even those with moderate to severe pain—do not become depressed,” he says.

For more information, visit the American Chronic Pain Association’s website or check out the resources available from the American Psychological Association.

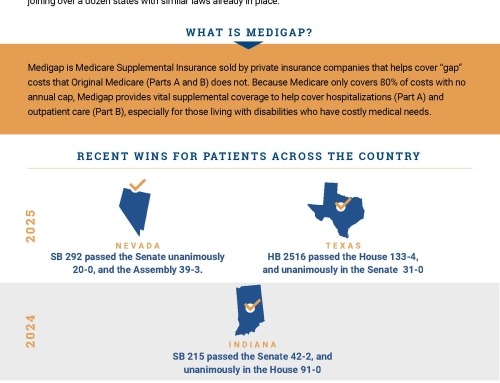

This article was developed jointly by the American Psychological Association and Dialysis Patient Citizens Education Center as part of a partnership to educate dialysis patients and their families on the psychological and emotional aspects of managing kidney disease.