By Julie Crandall, CBCS, CMAA, Patient Ambassador, DPC Education Center Board Member

How was it to grow up with end-stage renal disease (ESRD)? Since I didn’t know any other way; for me, it was normal. I can tell you that in my case, my family was the most important people that helped me navigate childhood. It helped that they didn’t treat me like the ‘sick kid’ of the family; I was a daughter and a little sister. I didn’t know what to focus on for this article. It was difficult to narrow down my childhood with ESRD and dialysis to write this article. I hope that what I chose to focus on will help others.

I was diagnosed with ESRD when I was seven years old. I vividly remember my parents sitting me down in the spare room of my grandparents’ house to tell me I had to go to the hospital. I didn’t know anything was wrong with me. My parents noticed signs that something was wrong. My small size wasn’t a red flag; I had a genealogy of small-stature family members in my extended family. My mom has told me that two of the red flags were: 1) I was walking like “an old man,” and 2) I was getting bloody noses. My official diagnoses are one kidney with hypoplasia (normal kidney but does not grow as I grow) and one kidney with dysplasia (short version: kidney did not develop properly). They were both birth defects that were not discovered until I was seven.

I am very grateful I wasn’t diagnosed earlier. We would have lived waiting for the day I would get sick; waiting for the day I would have to start dialysis. I got to be a normal little kid, without worrying about what the future held.

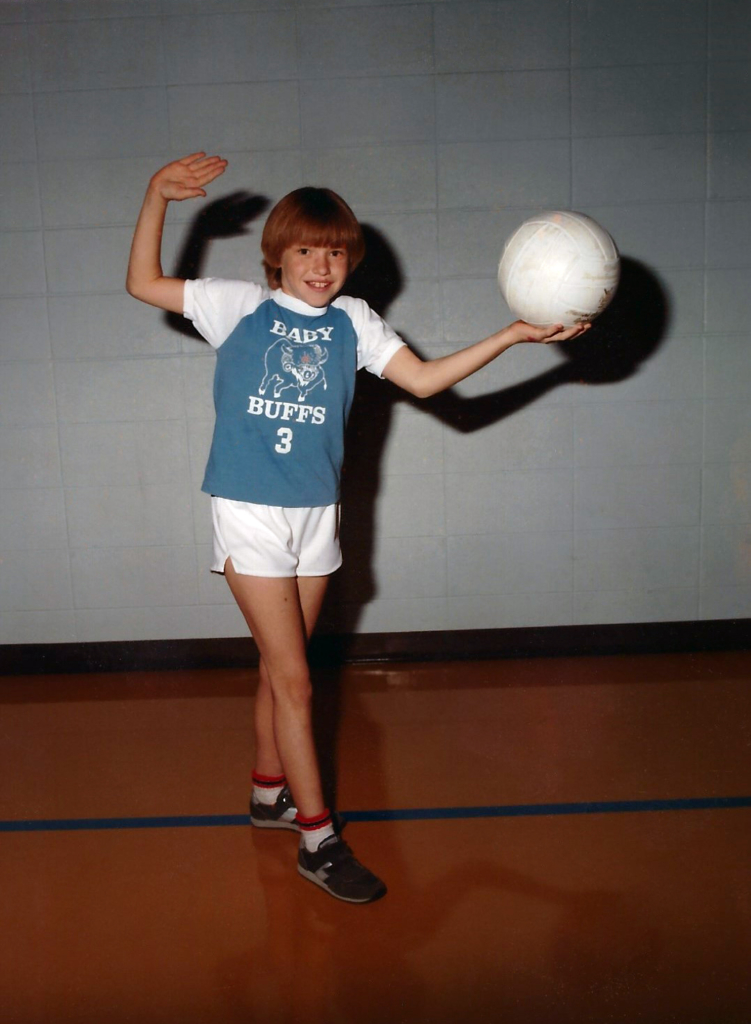

After I had my first peritoneal dialysis (PD) catheter implanted at eight years old, I was up playing volleyball with a blown-up latex glove with my roommate’s siblings. I honestly don’t remember it being a traumatic thing, starting on dialysis. It was a new way of life for me, and I do remember having to miss out on slumber parties with friends because I had to be home to dialyze at night on my machine. I didn’t want to be different from other kids. I remember one incident in PE class in probably fifth or sixth grade. I was on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) at that point. I would fill with dialysate in the morning, and the empty bag would be rolled up and held to my lower back with gauze fish-net. (Sorry, I can’t remember what it was called.) We were walking off the court and a classmate saw my empty dialysate bag on my lower back. I was so embarrassed, I changed the subject fast and ran away.

A couple years later at age 13, I had to change to hemodialysis after multiple bouts with peritonitis. I was terrified—more specifically of having two large needles stuck in me three times a week. There was one patient in particular, John that helped me with the transition. While I did have fantastic doctors, nurses and technicians at the pediatric unit, it was having another kid my age to talk to, who could relate what I was going through, that made it a little less scary. I don’t remember exactly what he did to make the transition easier, but I remember we played poker a few times. He was 15, so it was cool to beat him, repeatedly.

Because there was not a unit close to my home in Proctor, Colorado, my family moved to Ft. Collins so I could have a unit where I could do dialysis. It was a difficult time; my dad was going back and forth between our new and old home for work. It was a sacrifice for my older brother, who had to move during his senior year of high school. It was difficult for me to move from a school with 28 kids in my class to a school where there were over 300. I didn’t make many friends because I was never in two classes with the same kids. It was difficult to make friends when I had to miss so much to go to dialysis three afternoons a week, and I couldn’t do some things that other kids could. I did make a very good friend at church who would visit me at dialysis, or we would talk on the phone while I was at dialysis. Keep in mind, this was long before cell phones. The staff would have to bring a phone and stretch the cord to be able to reach my chair.

Fortunately, my parents found a nurse back in my hometown that trained to be my home dialysis nurse. We got to move back to my childhood home; back to all my friends I had grown up with, in time to start my eight-grade year.

Near the end of my eight-grade year, my dialysis graft got infected, and it had to be literally dug out of my arm. I had a huge hole in my arm because they couldn’t stitch it up. It had to heal from the inside out since the hole was so big. I wanted to try out for the high school cheerleading squad. Unfortunately, because of my wound, I was not able to try out during my freshman year. Also, due to the size of the wound, when it did heal, it gave me my biggest scar at that time. I did whatever I could do to hide that scar. My friends and I would tell people I got in a knife fight to explain the huge scar. It was difficult for me to let people know I had a chronic illness. I wanted to cover up my illness no matter what.

When I was 15, I decided I wanted to get on the transplant list. My mom reminded me a few years ago why I decided it was the right time. I am a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. I was going to get to start dating at age 16, and I didn’t want to date and still be on dialysis. Another patient close to my age was there for me to talk to prior to getting on the list and to answer questions on what I could expect. Her name was Tracy; she was a huge help to me.

I was paged for a transplant at about 3:00 a.m. on June 13, 1987. One of my best friends was staying overnight with me, so we dragged her to the hospital, which was three hours away. I remember being rolled down the hallway, my mom and friend crying, and my telling them to quit crying because I was trying to check out the anesthesiologist. (He looked like Mike Horton on “Days of Our Lives.”)

I was able to start high school as a “normal” teenager, not having to worry about dialysis. I did gain about 40 pounds after my transplant because nobody told me that I would gain so much water weight due to the large doses of prednisone. Teachers that had known me for years did not recognize me. I was very blessed to grow up in a small community, with friends I’d known for most of my life. I didn’t have to worry about being bullied. I was teased, but I had been teased my entire life (three older brothers). It was never mean, and no one ever made me feel bad about myself.

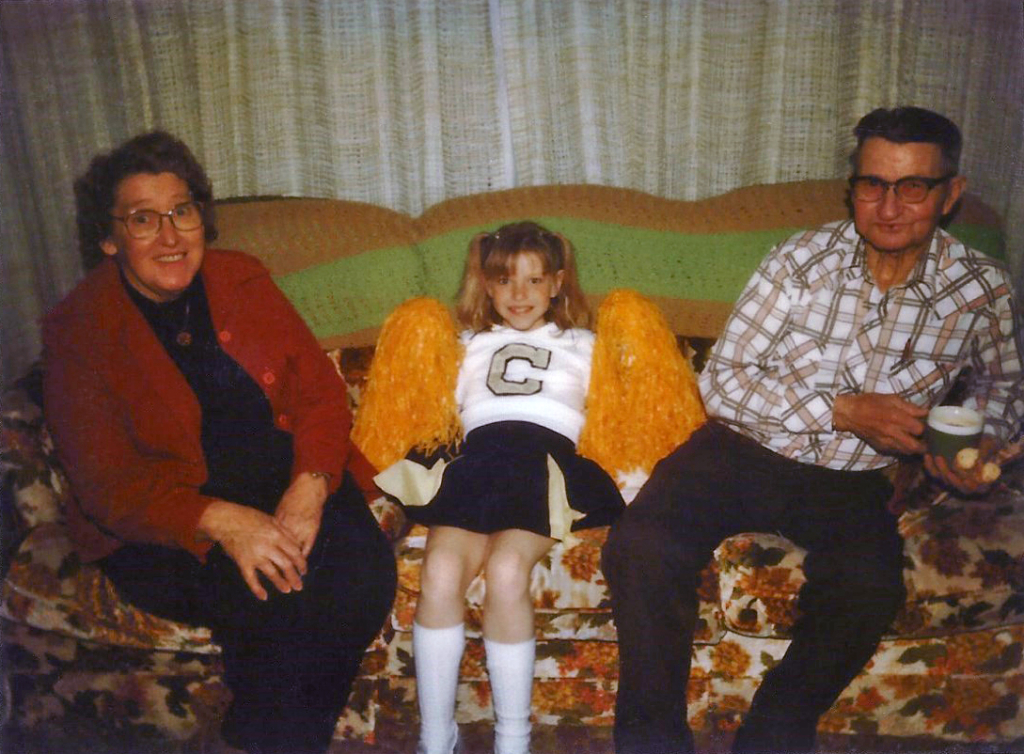

At the end of my freshman year, I made a dream come true when I tried out for the cheerleading team. I made the cheerleading squad for my sophomore year of high school. I felt like a ‘normal’ teenager, doing everything teenagers could do.

Then, about a year and a half later, my kidney went through rejection. I went back on the transplant list during my junior year of high school. The morning of my high school’s junior/ senior prom, April 21, 1990, I was paged for a transplant. I called my best friend to let her know I was going to miss the prom. I didn’t have any way to reach my prom date; he didn’t have a home phone. Once again, this was before cell phones were commonplace.

This kidney was a great match. I was out of the hospital in three days and able to attend a class movie a week after. I remember walking down the hall, and two of my classmates turned the corner and saw me. One of them asked me, “Didn’t you just have a transplant?” They were shocked to see me back at school already. The mistake I made was thinking I was ‘healed.’ I was feeling the best I had felt since I was seven years old. I took advantage of how I was feeling. I didn’t take my medications as I should have; I didn’t get a monthly blood test as I should have. I ended up losing the kidney after about two and a half years. It was a difficult lesson to learn; it almost cost me my life. It did cost me my kidney. I chose to wait a few years before I even thought about going back on the transplant list. I knew I had some maturing to do. I needed to know I was ready to do all that was necessary to stay healthy and take care of myself.

I want to share a couple of things I have come to realize over this childhood filled with challenges and victories. 1) I learned to keep going after my dreams. Never give up on what you want to accomplish. You can do it. 2) I learned to be proud of every scar I have. I earned every scar by surviving. Each scar tells a story of how strong I am and of how much I have survived. Never be embarrassed about any scar you have. 3) Transplant is NOT a cure, but it is a new way of life. It is important to follow what your doctors tell you: go to your doctor appointments, get monthly blood tests and take your medications as prescribed. 4) There are others out there who have gone through what you are going through. Talk to others. Please know that you are not alone.

This is a brief chapter in my life with ESRD. I hope it can help at least one person. I am here to help if you have questions or need to talk about dealing with ESRD.